Arriving a little late to the triphasic training party, I began using this methodology with my high school teams and athletes about five or six years ago. I was happy with our strength programming but am always looking for ways to improve what we are doing and enhance our performance. The time had come for a change. After researching triphasic training a little more, it seemed like it could be a good transition into tweaking our programming while ultimately increasing the power of our athletes—we were getting really strong but were moving those weights very slowly.

Triphasic seemed like a logical step to take in training to increase our power. With this post, I’m going to explain a little bit about what triphasic training is and how I apply it with my athletes.

I started down the triphasic path by reading about it online and watching interviews with the method’s creator, Cal Dietz. It quickly became clear to me that I needed to buy Cal’s book, Triphasic Training Manual, to fully grasp this system. I’ve known Cal for a long time—I was an intern with the strength and conditioning staff at the University of Minnesota in the early ’90s. I would periodically stop by the weight room when I was back on campus and met Cal when he was a grad assistant. After he got hired full-time at the U of M and started putting his stamp on things there, it was always a learning experience for me when I would visit.

Cal is always open and excited to share what he is currently doing, and to be honest, half of what he told me went right over my head. But one thing was always clear: he spent a ton of time researching and really pushed the envelope on being cutting edge in the field of strength and conditioning. And he tested everything. Whether or not I truly understood all the science behind what he was doing, I knew this was a coach I could trust. If he said something worked, it worked.

For those who may be unfamiliar with triphasic training, the method basically incorporates specified rep tempos, focusing on a certain phase of the movement or a certain type of muscle contraction:

Now, slow eccentric training and isometric workouts have been around for over a hundred years. Charles Atlas’ “Dynamic Tension” workout program, which gained popularity in the 1920s, was an isometric training program. Cal fully admits he didn’t invent this type of training, but I think he certainly deserves credit for putting these things into a usable system that can be easily applied.

Triphasic started, as Cal tells it, with two of his throwers at the University of Minnesota. These two athletes were virtually the same in every way: same age, same size, same background, and the same strength maxes. They were practically identical. One puzzling difference, however, was their performance in the throwing circle. One was a nationally ranked shot putter throwing 65’ while the other was just average in the Big Ten throwing 55’. After doing all kinds of testing with these two athletes, he concluded that the difference came down to power output; more specifically, the rate at which power could be generated.

Further study revealed that the rate and speed of the eccentric contraction had a direct correlation to the rate and speed of the concentric contraction of that rep. The faster the eccentric contraction (under control), the faster the concentric contraction. The opposite was true as well: the slower the eccentric contraction, the slower the concentric contraction. You cannot counter a slower eccentric with a faster concentric. It doesn’t work that way. Fast “up” requires fast “down.” And since Power = Work ÷ Time or Force x Velocity or Strength x Speed, weights moving at faster speeds result in higher power outputs.

So, triphasic training was basically born from the goal of developing the strength needed to decrease the total time spent performing reps (eccentric time + concentric time). That is done by focusing on bar speed while also developing strength in all three phases of a repetition:

The focus of lifting weights is commonly just that—the actual lifting of the weight, or concentric contraction. Triphasic trains all three aspects of the movement and results in greater power output and greater carryover to the field of play for the athletes.

*Note: Other goals of triphasic training are to create stress on the body and central nervous system and to train the CNS for its role in muscular power output, but those are aspects for another post.

The nice thing about triphasic is that the principles can be applied to existing programs. You don’t have to reinvent the wheel, or totally abandon what you are doing and start from scratch with something new. You can keep what you are doing and adjust it with triphasic. In my first programming attempt with it, I basically took one of my current off-season programs, kept all the exercises, and just started tweaking the weeks. I added the rep tempos and adjusted the intensities and volumes for each workout.

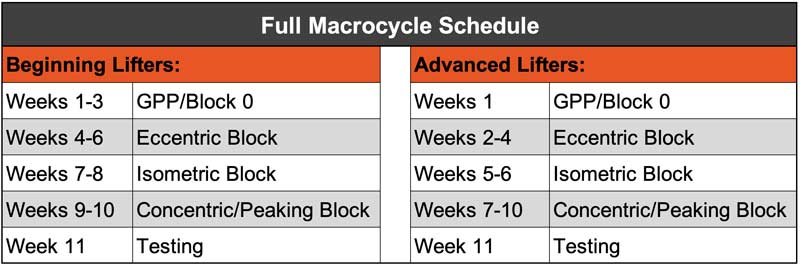

A full training macrocycle is typically 3-4 months but can be extended longer. Within that macrocycle, there are 4-5 mesocycles, each lasting several weeks:

In Farmington, we are on trimesters for our physical education classes. Here is a typical macrocycle for our weight training classes:

One nice thing about being on trimesters as a PE teacher and strength and conditioning coach is that the time frame and calendar match up very closely with our sports seasons. Off-season athletes in our strength and conditioning program follow the same schedule (and lifting workouts) as our classes. The schedules for in-season teams are close to this, but adjusted slightly based on the length of the season, post-season expectations, and competition schedule, among other things.

After buying the triphasic book and getting a handle on the science behind the process, I decided to jump right in and start programming our eccentric block. I’m a big believer in doing the same things that I ask my athletes to do. I think it helps tremendously to know what they feel during workouts because it’s much easier to coach if I’ve felt those same things myself. This was especially important when starting triphasic, so I did all the workouts a week before my athletes did them. At the same time, I poured over and re-read the eccentric chapters again until I was confident things were ready for my own lifters and that I could effectively communicate expectations and outcomes.

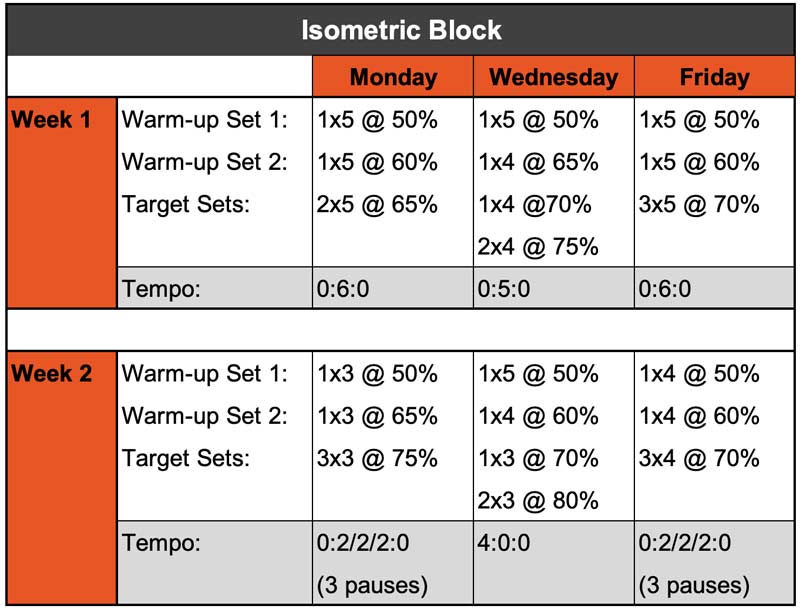

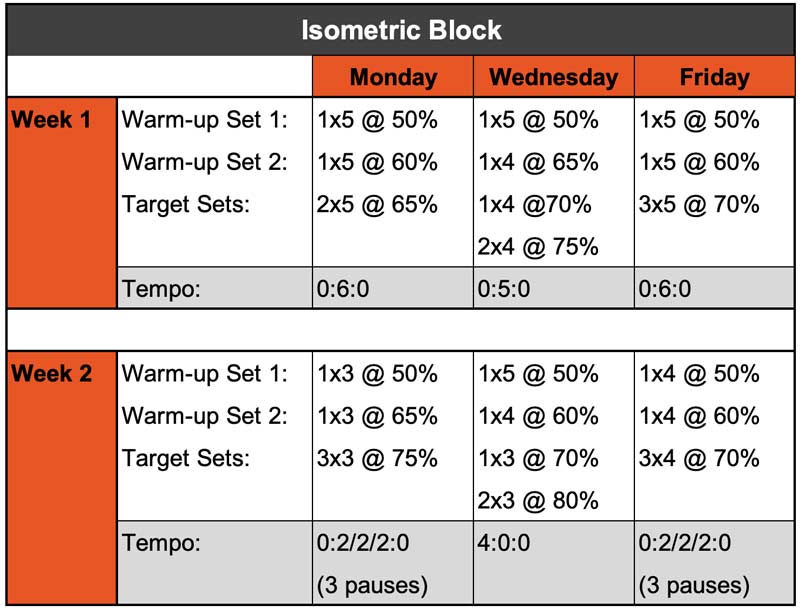

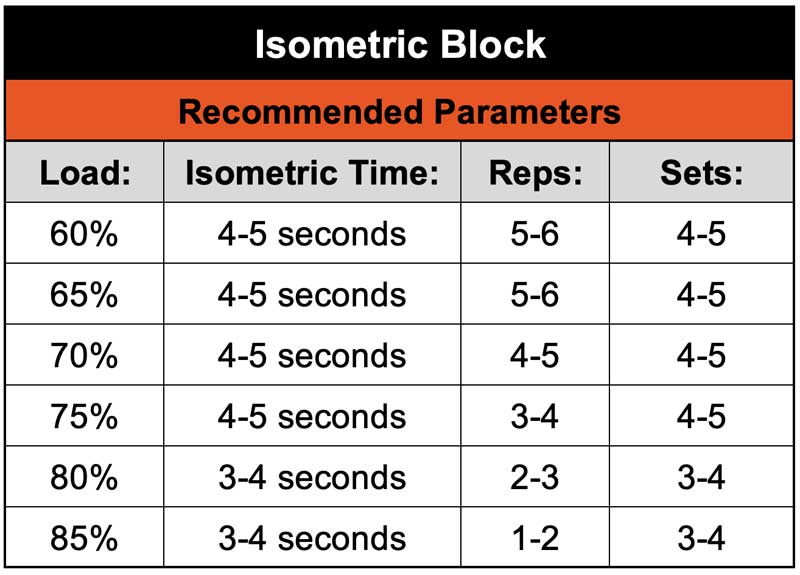

After two weeks of the eccentric block, I did the same thing when we switched to the isometric block for the next two weeks. I performed the workouts myself a week ahead of time, made adjustments, and did a lot of re-reading of the isometric chapters in the book. We then followed that up with the concentric/reactive/peaking block and tried some new approaches, some of which worked and some of which did not. I’ll get more into that shortly.

Here are nine key takeaways from the first full run-through:

1. Slowing things down. My original plan was to use this advanced training approach only with my advanced and experienced lifters. I quickly realized that triphasic is fantastic for beginning lifters. Beginners always seem to rush things in the weight room and are in a hurry to get things done. Slow eccentrics literally slow things down, giving them plenty of time to think about how they are moving and what they are feeling. This forces them to focus and concentrate on the movement a lot more. It also provides a great opportunity to emphasize working through a full range of motion. It’s hard to cut reps short if you are lowering the weight for five or six seconds. As a result, 6-8 second eccentric squats have helped our depth and form tremendously.

2. DOMS? I was fully prepared for some terrible soreness from all the eccentric work—it didn’t happen. In fact, two weeks was so tolerable that I added a third week to our eccentric block and have kept it ever since.

3. Iso challenges. Feeling confident after the eccentric block, I was crushed by the isometrics. They were way harder and caused way more muscle soreness than what I was expecting. The same was true for my athletes. Two weeks of isos is plenty.

4. One M-i-s-s-i-s-s-i-p-p-i. People count too fast when they are under load, myself included. What should have been a six-second down count or pause usually ends up being closer to four seconds. Timer apps or partners counting for each other work better. To counter this now, I actually program our tempos a second or two longer than what I want. If I want a six-second eccentric, I’ll program it for eight. If I want a three-second iso pause, I’ll program four or five seconds. That way if they count a little fast, they end up getting what I want. If they go the full prescribed length of time, it’s bonus time under tension for them.

5. Ease of use. Slow eccentrics are pretty straightforward. They can also be used with Olympic lifts but in a limited fashion.

6. Room for creativity. There are more options for isometric pauses and they can be implemented in numerous ways.

7. Concentric speed. I need to constantly be preaching about concentric bar speed and moving as fast as possible.

8. Removing constraints. My athletes were super excited to get back to full-speed reps with the concentric/reactive/peaking block after finishing the eccentric and isometric blocks, and the weights were flying after putting it all together. Everyone is always amazed at how easy things feel at that point with weights they had previously considered heavy.

9. Simplify the labels. Cal’s four-digit tempo labeling system was reduced to three-digits. The four numbers in the system’s sequence represent time in seconds for each segment of a repetition:

I decided to drop the fourth number (pause at the top between reps), so 1:0:1:1 became 1:0:1 for us. I felt that starting out with the extra number was not needed and seemed overly confusing early on, giving my athletes too many things to think about. Taking it out simplified things greatly. If we eventually got to cluster sets, I could add that back in.

I’ve adjusted our eccentric block slightly over time. We now incorporate slow eccentrics with all lifts (or as many as possible). Our workouts consist of three primary lifts of the day that we always start with (because we have three stations to lift at) and I call these our Big Three. They’re a squat movement, an Olympic lift or variation or deadlift variation, and an upper-body push or pull. I initially started doing slow eccentrics with one or two of the Big Three. It was difficult and did apply more stress because of the extended time under tension, but it wasn’t overly stressful and certainly wasn’t too much for my lifters to handle. So, the next time through the entire training cycle, I decided to apply the slow eccentric to as many lifts as possible in our eccentric block: all of the Big Three lifts, as well as our auxiliary lifts if possible (3-4 movements per workout).

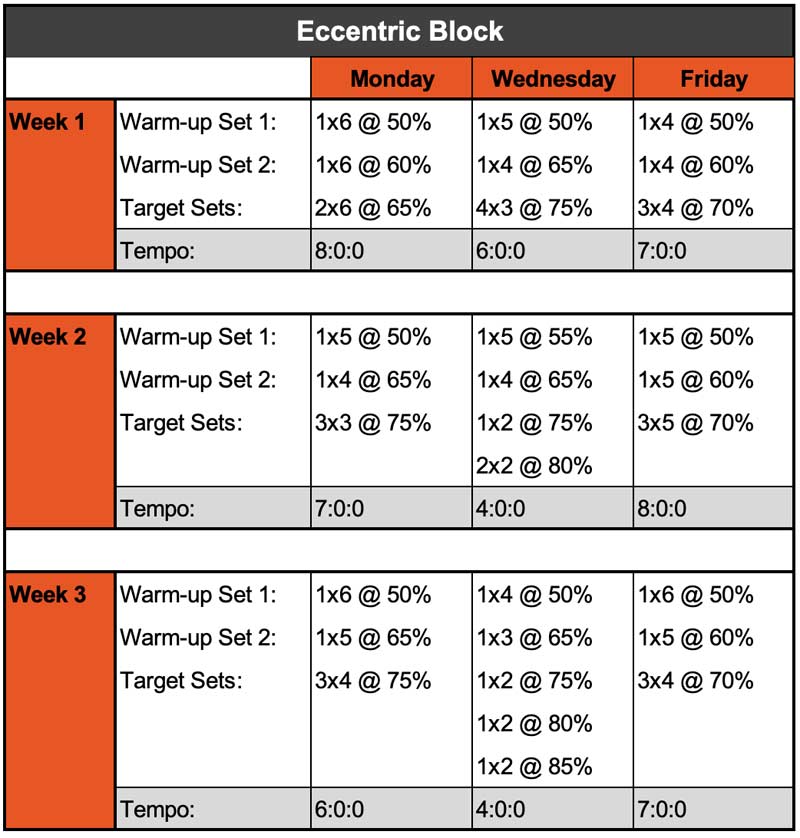

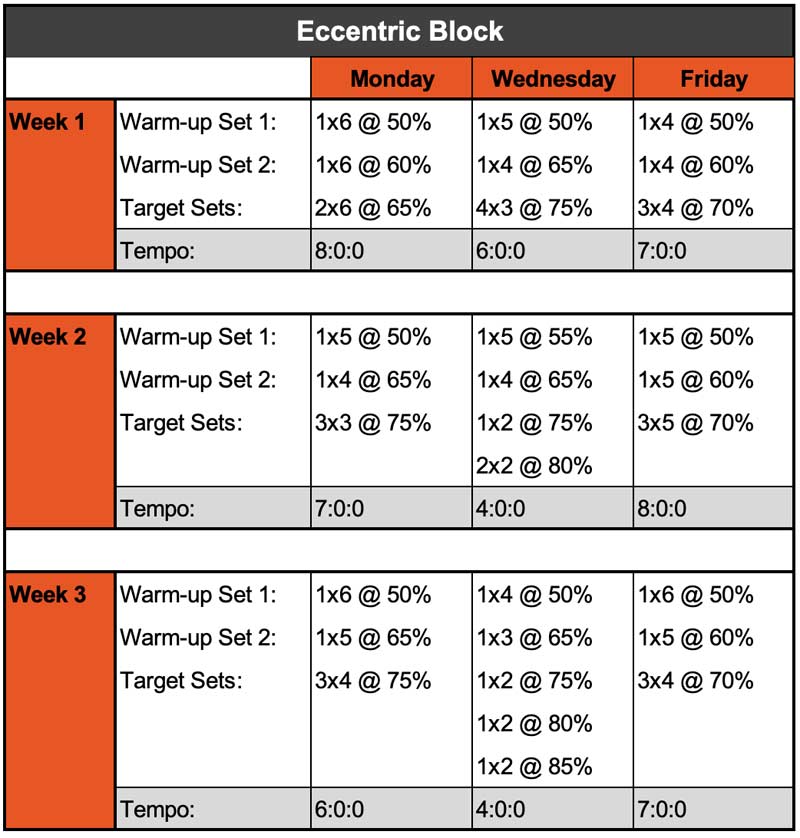

Below is an example of what our three-week eccentric block looks like and how we progress over that period. In a typical three-day training week, Mondays are usually our medium day, Wednesdays are the week’s heavy day, and Fridays are a higher volume day with lighter weights. I apply that approach for this training block as well, but I always start with the first day of the full block as very light. Day 1 of a new training block is always a learning experience, so I ease my lifters into that first day and then build from there.

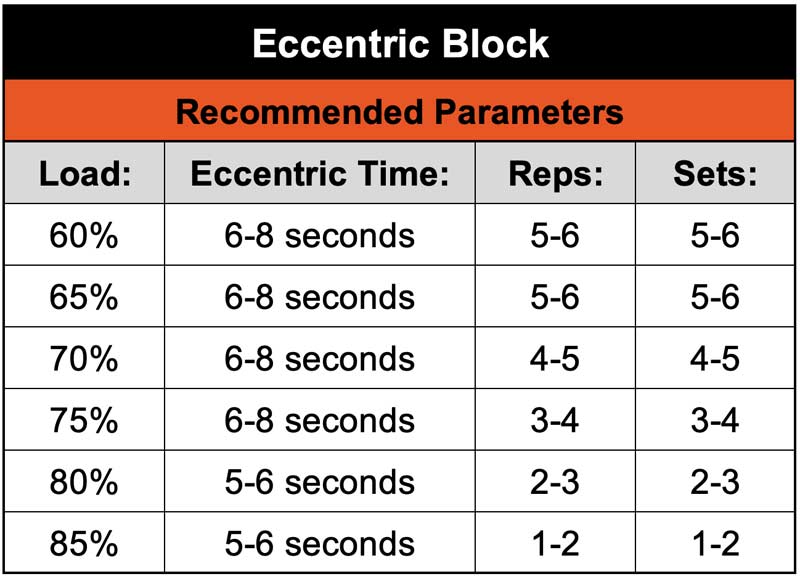

Key points for slow eccentrics:

I was feeling really good with how the eccentric block went and finished up. My athletes were also feeling really good, but also extremely happy to be finished with it and ready to move on to the isometric block. In my personal test run with the isometric block, I found it to be more taxing and resulted in more muscle soreness. My athletes did as well, so extending this block from two to three weeks was not going to happen. Just like our approach to the eccentric block, I try to include isometric pauses with as many lifts as possible for each workout.

There are several purposes for the isometric holds or pauses. One is to develop strength specifically at the point in the lift where the weight changes direction, or the point where eccentric switches to concentric. If you can improve the strength at that spot, the lifter should theoretically improve their ability to transition into that concentric phase quickly and more powerfully, increasing the power output of that contraction.

Another purpose is to remove the stretch reflex. Starting the concentric contraction from a dead stop makes the lift a little more difficult, similar to doing a box squat, in that the lifter does not get the aid of the stretch reflex from the muscles involved. More effort is then required to start the weight moving, which will increase strength and power development at that point where the weight is paused when switching back to normal speed reps.

The third (and most overlooked) purpose is using isometric pauses to train deceleration. Bar speed is critical during this isometric block. The eccentric contraction should be done as fast as possible, and then the lifter should be slamming on the brakes to stop the motion as quickly as possible. Lowering the weight slowly and slowly going into a pause defeats the whole purpose of using isometrics for triphasic training. It has to be done fast and the weight has to be stopped fast. That ability to quickly decelerate has a huge carryover to athletic performance in terms of improving agility and change of direction capabilities. I find myself using the cue “Down fast and stop fast” constantly during this block.

Key points for isometric pauses:

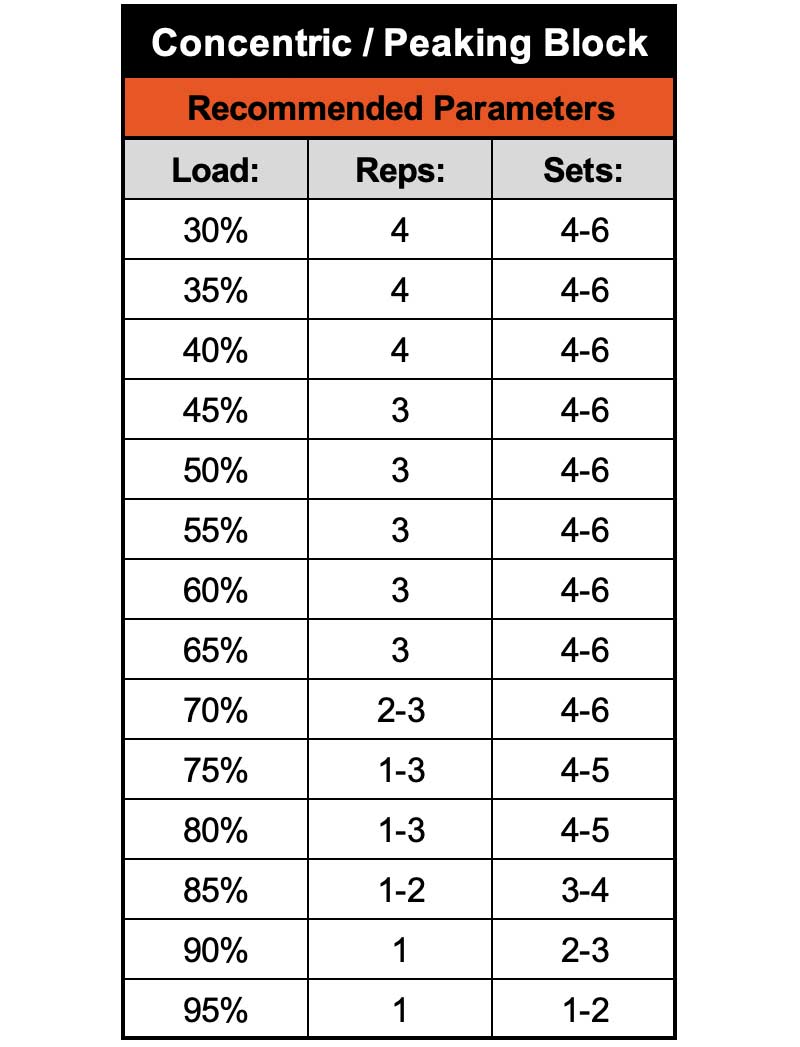

The first week of this block is what I call our “Off The Leash” week. No more restrictions, no pauses, nothing slow. Full speed reps. My athletes are always excited to get to this point, and the weights are flying. The discipline of following the program and rep tempos all comes together in this block and the payoffs are huge. Lifters are always shocked at how easy the weights feel when we get to this point, and this is when they really believe in the process. Buy-in from that point on is very easy.

In the Triphasic Training Manual, the concentric/reactive/peaking phase is actually two separate training blocks. Low reps with heavy weights follow the isometric block. Then, the true peaking for sport phase incorporates light weights with maximum speeds, along with some advanced training methods like French contrast, oscillatory reps, and others. With our physical education classes being on trimesters and off-season athletes being on a similar schedule, we only have time to move to a couple heavy weight weeks before finishing up. We do not include the really fast rep weeks, just because we don’t have enough time. If I had another 4 weeks, I would include that final peaking phase. With some of my in-season teams though, we do get to that at the end of the season—especially in the winter, because that’s a longer sports season for us in Minnesota compared to fall and spring.

In the book, the French contrast method is discussed extensively for peaking. This is something that seems to be very complicated and is something that I would only use with my very advanced lifters. Just doing contrast sets with two exercises has been very difficult for my athletes to do correctly in the past. Doing that with four very distinct and different movements seems almost impossible for us. Group sizes and training spaces combine to create limitations for our ability to do French contrast.

I think most coaches have their own established process for peaking, so I won’t get into the details of that in this post. One key point is to avoid going to muscular failure at any point. Below are the recommended sets and reps for various intensity levels. Quality reps are the number one goal during this block. Going to failure basically destroys the quality of everything that occurs after that point.

Going to failure basically destroys the quality of everything that occurs after that point, says @FarmingtonPower. Share on X

Over my coaching career, I’ve seen numerous trends come and go when it comes to programming and training methodology. I have changed my own programming over the years as well. Some were big changes, but mostly small things here and there like everyone else. Implementing triphasic training principles, though, has been the biggest game-changer for my athletes since I started in the field in the early ‘90s. Not only have our strength gains been tremendous, but the speeds at which the weights are moving have increased dramatically. Moving really heavy weights at really slow speeds is not very beneficial for athletes. We were getting very good at that. Triphasic has solved that problem for us and has resulted in powerful athletes that are now having more success in their sports as a result.

Hopefully this is enough information to at least get you started with using the triphasic training method. It really is a low risk/high reward change in weight room programming that can be easily applied. I highly recommend trying out a full macrocycle to see how it works. After that, I’m confident it will become part of your regular lifting approach.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Scott Meier is currently in his 22nd year at Farmington High School (MN) where he is a physical education teacher and the Head Strength & Conditioning Coach. He coached Farmington’s competitive weightlifting team for nine years, and in that time the Tigers earned four state team titles and produced over 40 individual state champions and multiple state record holders. Prior to that he worked as a personal trainer for six years. Until recently, Scott was a nationally ranked sprinter at the master's level and holds several track and field state age-group records. In 2020, Scott was named the NHSSCA Mid-American Region Strength Coach of the Year.

Great article, thank you for this explicit yet simple Tri phasic explanation. One question though if I may, when you state, “There are several purposes for the isometric holds or pauses. One is to develop strength specifically at the point in the lift where the weight changes direction, or the point where eccentric switches to concentric”, do you mean that the isometric hold should be performed at the point of actual reversal from eccentric to concentric? If so, that would mean full elbow extension for bicep curl, full shoulder overhead flexion for shoulder press, etc. all of which are at a relatively minimal stress point in the strength arc. Thanks again for your work.

if you are doing a 4 day training week in the summer, I am doing the following:

M-Squat

T-Bench

W-Hang Clean

R- RDL I have 8 weeks for summer S&C. How will you set that up?

What do you recommend for Judo, many variations in lifting, breaking balance, the pull or push, explosive entry, turn or fitting, the finish, .

how long are your rest periods between sets of the Eccentric, Isometric & Concentric. I have the Deitz book but can’t find recommended rest periods.